Dealing with Disruptive Behavior

“A master can tell you what he expects of you. A teacher though awakens your own expectations.”

-Patricia Neal

Introduction

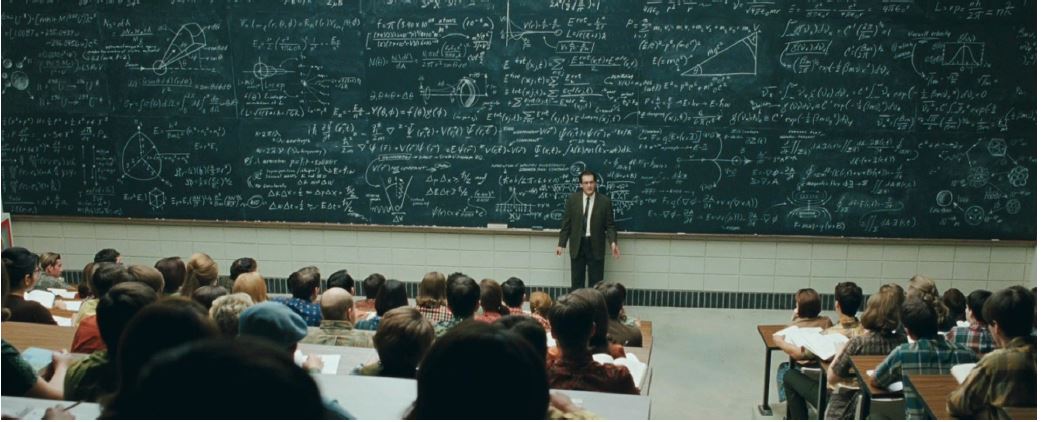

Disruptive, rude, and troublesome behavior has become increasingly prevalent in the college classroom. This publication has been developed to provide background on disruptive behavior, as well as to suggest techniques for preventing and/or coping with it. The goal is to enhance your classroom management skills, so you can create an environment that allows all students to learn and participate freely.

Broadly defined as repeated, continuous, or multiple student behaviors that prevent an instructor from teaching and/or students from learning (Akers), incivility is the opposite of courtesy, politeness, respect, and consideration (Rookstool 2). LCC defines disruptive behavior as the disruption or obstruction of teaching, research, administration, disciplinary proceedings, other College activities, including its public service functions on or off campus, or of other authorized non-College activities when the conduct occurs on College premises.

Not only do these troublesome behaviors disrupt and negatively affect the overall learning environment for the students in the classroom, but they may also contribute to an instructor’s stress and discontent. Although individual faculty interpretations and perceptions determine what s/he considers uncivil behavior (Holladay), the following are typical examples (Holladay; Reed; and Rookstool 2):

- arriving late and leaving early

- engaging in sideline conversations

- laptop use unrelated to class

- doing other coursework

- sleeping

- text messaging

- ringing cell phones and/or taking calls during class

- monopolizing classroom discussions

- ridiculing the instructor

- being argumentative and/or confrontational

- submitting assignments late and requesting frivolous deadline extensions

- wearing distracting attire

“Awareness of the focus of uncivil behavior ] is vital to our abilities to create spaces conducive for the learning of all students and productively engage them in sensitive topics of conversation and intellectual inquiry.”– Courtney N. Wright in Inside Higher Ed (2016)

Proactively Addressing Disruptive Behavior

According to the literature, appropriate behavior is best encouraged by clarifying expectations. Consequently, proactively avoid problems by clarifying your expectations and course policies on the first day of class. The most appropriate way to do this is in the syllabus. In addition to referring to LCC’s General Rules and Guidelines and the Student Code of Conduct and/or department- level policies listed on the Official Course Syllabus, you could enumerate your course policies on your section syllabus. You might include your policies and/or LCC’s policies on…

- attendance and consequences for missed classes

- tardiness

- missed deadlines/exams and procedures for making up exams or missed course work

- how/when to contact you when students will be late or absent

- use of cell phones, etc. At LCC, the use of all phones during class is

Additionally, you could include a statement in your syllabus. The following example is required on all syllabi at Eastfield College in Dallas, Texas:

“Since every student is entitled to full participation in class without interruption, all students are expected to be in class and prepared to begin on time. All pagers, wireless phones, electronic games, radios, tape or CD players or other devices that generate sound must be turned off when you enter the classroom. Disruption of class, whether by latecomers, noisy devices or inconsiderate behavior will not be tolerated. Repeated violations will be penalized and may result in expulsion from class.” -(Rookstool 31).

Within the first two weeks, you might also consider the following suggestions to encourage appropriate behavior.

- Discuss your “ground rules” – or, better yet, have the students develop them so they feel ownership for them. For ideas on how to have your students develop “ground rules,” see the CTE’s Teaching Tip, “Establishing Ground Rules on the First (or Second) Day of Class” Teaching Resources.

- Reduce anonymity by letting students know some of your personal interests and learning about theirs (Carnegie Mellon).

- Connect with your students by learning their names. For ideas on learning students names, see the CTE’s Teaching Tip, “What’s in a Name? Strategies for Remembering Students’ Names” at Teaching Resources

- During class, stand up and/or walk around the room.

- Be extra firm on all matters the first day and weeks to set the tone. You can always be more flexible later, but it’s difficult to do the reverse.

- Use good-natured humor and avoid sarcasm

- Change classroom activities frequently and give 10 minute breaks every 50 minutes to allow students to reset their attention, use the restroom, etc.

- When disruptive behavior occurs, respond immediately and consistently, before a pattern develops. How you handle the matter will depend on the nature of the problem, the student(s) in question, and what feels most comfortable to you (Carnegie Mellon).

- Keep regular office hours and/or invite students to email you with questions and concerns.

- Seek ongoing feedback from students using Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs). CAT ideas from University of Kentucky

- Model the appropriate behavior. If you want papers turned in on time, promptly return them, etc.

Again, many problems can be thwarted by using the proactive measures discussed above. Nevertheless, troublesome behaviors will undoubtedly occur. Following are several categories of disruptive behavior and strategies for addressing them.

Responding to Interruptions

(e.g., arriving late, leaving early, packing up early/noisy, answering cell phones, etc.)

- Begin and end class on time. If you frequently let students out early, they will begin packing up before the class is over.

- Reserve some important points or classroom activities (i.e., quizzes, assessment activities such as “One Minute Papers,” writing exercises, distribute study guides or important handouts, etc.) until the end of class to minimize packing up early(Nilson 47).

- Use class time constructively. Make sure the content addressed and the learning activities are crucial to attaining the learning outcomes (Reed).

- Early on, refer to LCC’s policy on cell phones (or you may have your own cell phone policy). Note: video cell phones are prohibited in locker rooms and restrooms.

“Student General Rules and Guidelines” at https://internal.lcc.edu/catalog/ policies_procedures/studentrulesguidelines.aspx. In addition, you may want to include the following verbiage: All cell phones and electronic devices must be out of sight and turned off or set to courtesy mode before class begins. Students with a crisis should advise the instructor before class.

“It is what we think we know already that o.ften prevents us from learning.”

– Claude Bernard

Responding to Sideline Conversations

and other inattentive behaviors.

- Maintain your composure and model professionalism when addressing offensive behavior. Don’t embarrass students, but do address the behavior as soon as possible. Delaying your response may be interpreted as condoning the

- Move closer to the talking students; as soon as they stop talking, instantly move away to reinforce desired

- Rather than warn particular students, consider a general word of caution to the entire class (e.g., “We have too many conversations at the moment; let’s all focus on the same topic”).

- Try a long dramatic pause. If a dramatic pause doesn’t work, say something general like “I really think everyone should pay attention to this because…” or “I am having difficulty concentrating while there is talking and your classmates might be as well, so please wait until the break or share your conversation with the rest of us.”

- Ask the disruptive student(s), preferably during the break or after class, to make an appointment to see you. Tell them how their talking is affecting the rest of the class.

- Ask a nearby student a question so that the discussion is near the student(s) of concern.

- Make eye contact.

- Lower your voice. This causes them to become more obvious in contrast to the other students. Consequently, they may stop talking on their own, or other students may ask them to be quiet (Pike and Arch 71).

Responding to Monopolizing Students

and/or the domineering students.

- Say: “That’s an interesting point. Now let’s see what other people have to say. ”

- Give the monopolizing individual attention during breaks or before and after.

- Without turning your back on the students, prepare for the next activity (i.e., begin handing out papers, etc.). This signals to the student that you are ready to move on to another topic or idea.

- Interject with a summary when students go off on a tangent and/or ask others to speak (Silberman 30).

- Take advantage of the monopolizers’ pauses. While making eye contact, thank them and direct a question to someone else, preferably in another area of the room (Pike and Arch 72).

- Prior to asking a question, tell the students that you will be looking for ‘X’ number of hands before you select someone. And/or, when you pose a question, ask how many students have a response and call on someone (else) whose hand is raised.

- From time to time, suggest that only students who have not spoken or answered a question raise their hand.

- On occasion, distribute a certain number (e.g., three or four) of colored paperclips, tokens, or poker chips. Once a student makes a contribution to the discussion, they should put a clip out in front of them. Once they use up their allotted clips, they cannot talk any more. This might help the dominant students save some comments for other topics.

- If you speak to a student outside of class regarding their behavior, tell him/her that as much as you appreciate their input, it would be helpful if they could hold some of their comments until others have been heard (McKeachie 255).

- Physically involve the monopolizer by giving him or her a task such as posting group responses on flip chart paper or the board, distributing handouts, etc.

- If someone is monopolizing a small group, approach the group and kneel down so that you are at eye level. Make eye contact with each group member and remind the group that they have ‘X’ number of minutes left. Look directly at a specific group member and say “Please cover these two points (name them) and try to ensure that everyone in the group has contributed” (Pike and Arch 55-56).

“The ideal teacher guides his students but does not pull them along; he urges them to go forward and does not suppress them; he opens the way but does not take them to the place.” – Confucious

Responding to Un-engaged and Withdrawn Students

- Let students know in advance that everyone will be expected to answer questions and participate in discussions. Have a discussion about what is considered a good/bad discussion. Students become more engaged when they internalize the importance of discussions and participation (Eng 4).

- Help students prepare to talk by having them write before and after discussions. This “puts focus on developing ideas, rather than merely performance” (Eng 4).

- Make eye contact with inattentive students.

- Stand near them from time to time, but don’t hover.

- Change it up. Vary teaching strategies from group discussion to individual written exercises or a video

- Give positive reinforcement for participation.

- If a student appears shy, make a point of getting to know him/her during breaks. You might even ask them a question about what is being discussed. If you are impressed with their response, you might ask if they would be willing to share this insight with the class after a break.

- For paired work, pair a shy or introverted student with a moderately outgoing student rather than a dominant one.

- Ask students to write a self-evaluation about their perceived strengths/weaknesses at the beginning of the semester. Then you can call on them about something they have interest or expertise in (Eng 4).

- Ask the class to write “One Minute Papers” and ask the inattentive or shy students to share theirs.

Responding to Other Disruptive Behaviors

(e.g., asking unrelated questions, trying to trip you up, etc.)

- If a student is trying to shoot you down or trip you up, consider acknowledging that this is a joint learning experience, and/or admit that you don’t know the answer and redirect the question to the group or the individual who asked the question.

- If some students have a tendency to ask questions to get the class off track, designate a place on the board as the “Parking Lot” and list their questions there. Let them know that if there is time at the end, the questions will be addressed.

- If a student is overtly hostile or resistant, realize that the hostility may be masking fear. Remember to maintain your civility and consider any of the following:

- building upon what has been said versus disagreeing

- allowing him or her to gracefully retreat from the confrontation

- talking to him or her during the break

- as a last resort, privately asking the individual to leave the class for the good of the group

- If a student is openly griping, consider

- pointing out what can and can’t be changed

- validating the point

- indicating time pressures

- indicating that you’ll discuss the problem with the student

Responding to Extreme Cases of Disruptive Behavior

In addition to the common behaviors listed above, there are rarer incidences of extreme uncivil behaviors – behaviors that are threatening or harmful. Examples include:

- being verbally abusive

- using profanity and/or pejorative language

- being intoxicated or using drugs

- using intimidation, harassment, and physical threats

The sorts of behaviors mentioned above are often the result of stress, mental health issues, and the like. While occurring infrequently, it is your responsibility to stop student behaviors that endanger either themselves or others. The recommended course of action in such situations is to remain as calm as possible, create distance between that student and the rest of the class, and get support from campus Police and Public Safety (483-1800) immediately. In addition, as soon as possible, contact the Office of Student Compliance (483- 1167) and your Associate Dean, Coordinator, or Program Director. If it’s possible to enlist the assistance of a colleague in getting the help that’s needed, that is preferable, so you or the class are not left alone with the student.

Listed below are the departments and programs at LCC that can assist with various problems and issues.

Student Conduct Reporting System

The Office of Student Compliance has implemented a Student Conduct Reporting System.

Issues that should be reported through the Student Code of Conduct system include disruption of teaching, plagiarism or cheating, threats, and any other behavior that would violate the LCC Student Code of Conduct.

Behavior Intervention Team System

Behaviors that should be reported through the BIT form include instances, such as talk of suicide or suicidal action, threats of a weapon on campus, uncharacteristic alcohol and drug use, or overall unusual behavior, etc.

To file a report regarding an alleged Student Code of Conduct violation, or to submit information (BIT report) to the College’s Behavior Intervention Team(BIT), visit BIT and Student Code of Conduct Reports

Campus Resources

| Office of Student Compliance | (517) 483-1167 |

| Police and Public Safety | (517) 483-1800 |

| Center for Student Access | (517) 483-1924 |

| Counseling Services | (517) 483-1924 |

| Student Life | (517) 483-1285 |

| Adult Resource Center | (517) 483-1261 |

| The Learning Commons | (517) 483-1206 |

References

Akers, Stephen J. “Managing Classroom Behavior: Rights of Faculty and Students.” Office of the Dean of Students. Purdue U., 2006. Web. 16 July 2010.

“Addressing Classroom Disruption.” Student Conduct. Butler U., 2008. Web. 12 July 2010.

Carnegie Mellon University: Eberly Center, Carnegie Mellon University, 2016, www.cmu.edu/teaching/ solveproblem/index.html. Accessed 14 Aug. 2018.

Eng, Norman. 26 Apr. 2017.

teachlikeachampion.com/blog/teaching-college-

Nilson, L.B. Teaching At Its Best: A Research- Based Resource for College Instructors. Boston: Anker, 1998. Print.

Pike, B., and Dave Arch. Dealing with Difficult Participants. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass, 1997. Print.

Reed, Rosalind. “Strategies for Dealing with Troublesome Behaviors in the Classroom.” National Teaching and Learning Forum. 6.6 (1997): n. pag. Web. 13 July 2010.

Rookstool, J. Fostering Civility of Campus. Washington D.C.: Community College, 2007. interview-norman-eng/. Accessed 14 Aug. 2018., Print,Silberman, M. Active Learning: 101 Strategies to

Holladay, Joanne. “Managing Incivility in the College Classroom.” Division of Instructional Innovation and Assessment. U. of Texas Austin, 2009. Web. 12 July 2010.

McKeachie, W. J. Teaching Tips. Lexington: D.C. Health, 1994. Print.

Teach Any Subject. Needham Heights: Allyn, 1996. Print.

Wright, Courtney N. Inside Higher Ed, Inside Higher Ed, 4 Oct. 2016, www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/05/26/ seasoned-educators-weigh-not-losing-control- class. Accessed 14 Aug. 2018.

Provided by the Center for Teaching Excellence — Updated 2020